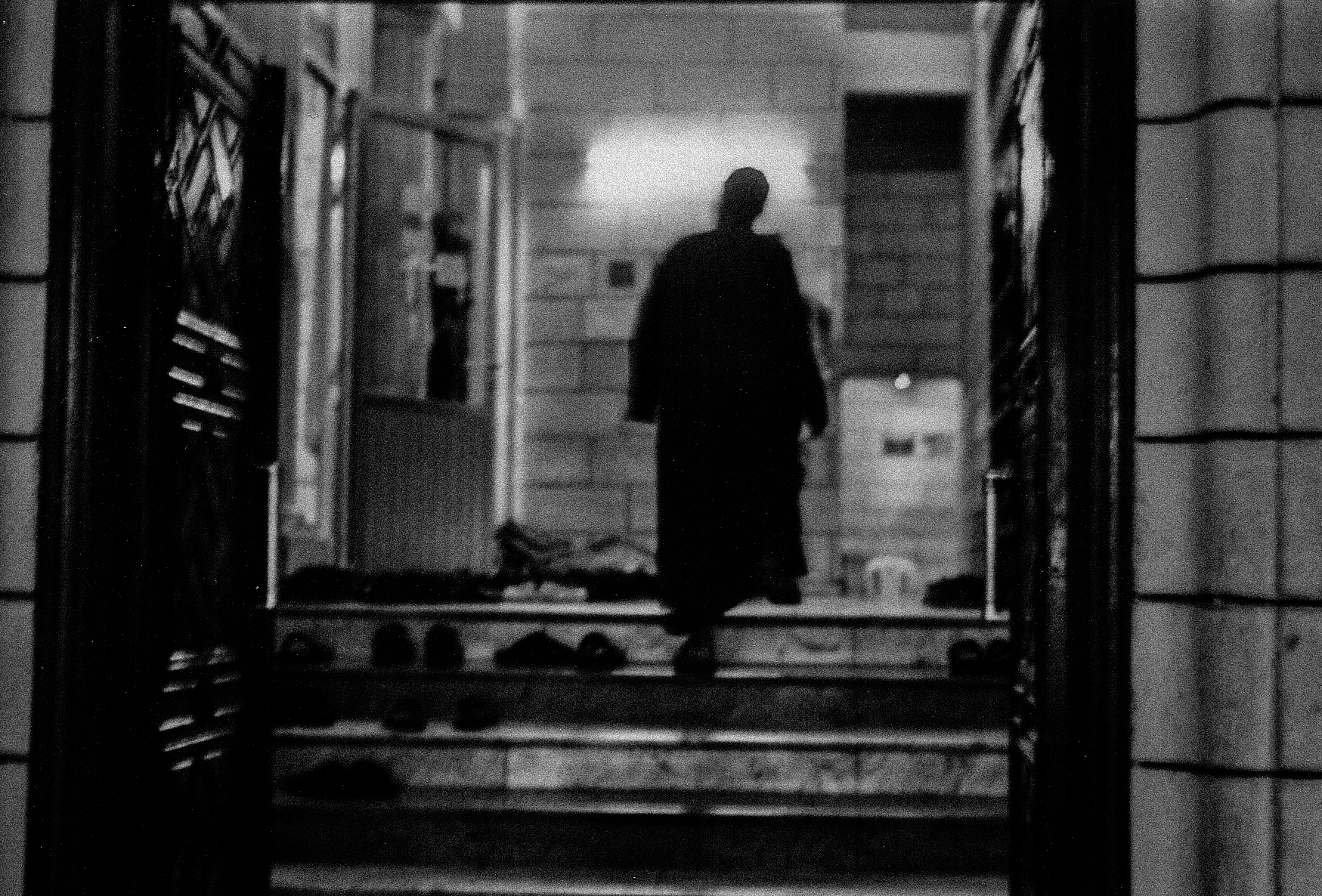

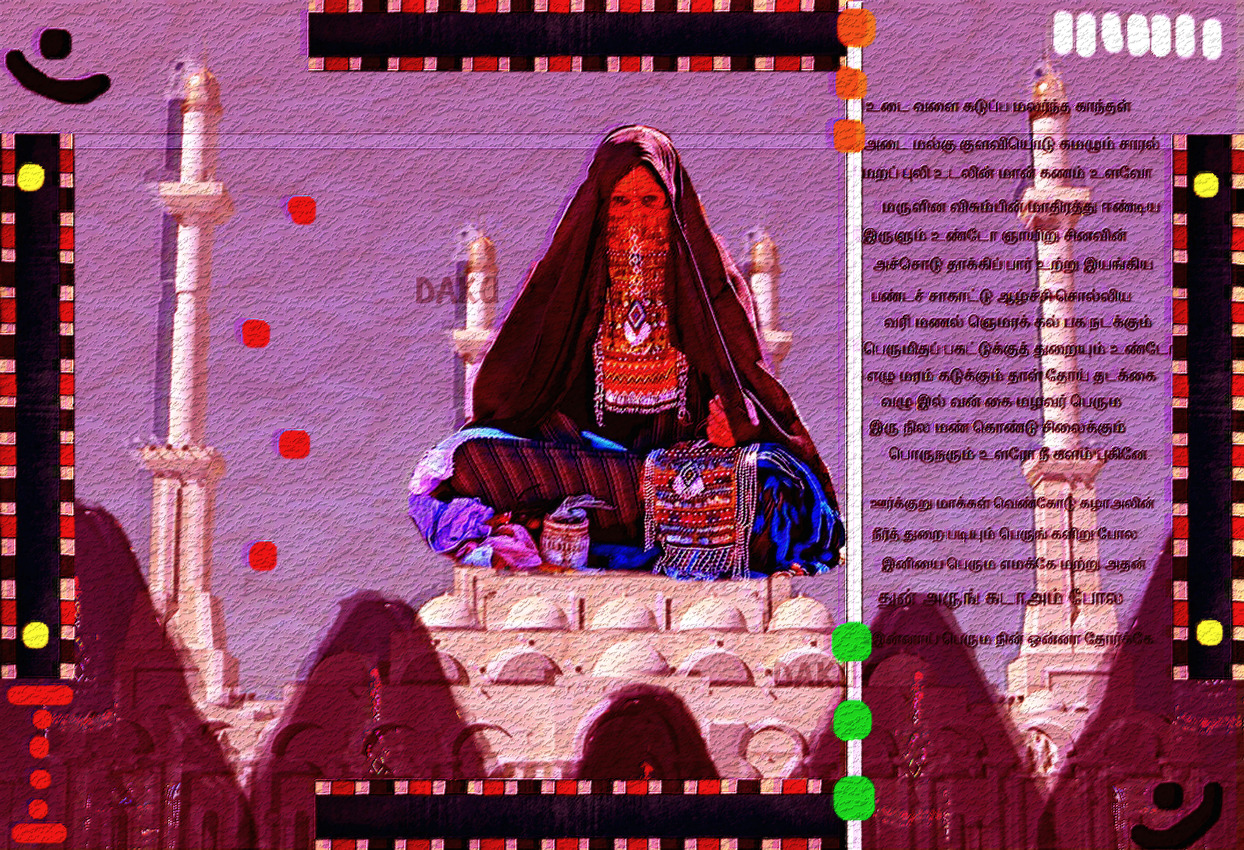

For this photoset, I went to the souq (Market) of Mubarkiya, the oldest known souq in Kuwait, predating the rapid urbanisation that swept the country during the 50’s after the discovery of oil. Within the old brick and concrete roads of the souq lie the smells of old Kuwait: fishmongers, butchers, fruit sellers and fabric shops, right in the heart of Kuwait’s booming downtown financial district. This juxtaposition of history is also reflected through market goers; selfie sticks and Segway scooters alongside old dates sellers and incense merchants; fathers taking their children to the old coffee shops to drink tea and tell the stories their fathers told them; families eating kebabs and shawermas in the same restaurant they’ve been going to for the past 30 years. The character of the souq is reflected upon the various nationalities of merchants there: Indian Bohra gold sellers, Iraqi and Iranian fruit and food sellers, Egyptian butchers, and Syrian fabric sellers. Mubarkiya is a microcosm of Kuwait’s cosmopolitan history.

My fascination with photographing the banal led me to conversations and photos with the various nationalities that inhibit the souq. A Syrian fabric shop owner, the one who is posing with a cigarette in his mouth, came to Kuwait at a young age and started working with other Syrians in the business. He still has family back in Syria and, as he looked away (perhaps out of respect) and inhaled his cigarette, told me about his attempts at applying for a visa for his nephew in order to get him out of Aleppo. His pain was tangible, it almost had a taste of stale cigarettes chain-smoked to help him cope. A pain reflected by his blackened out face; a face succumbing to hopelessness, numbness. The unfortunate banality of his pain contrasted by his sense of humour when he told me he chooses to dress smart because no one would buy from a messy looking merchant. He wore a bright patterned maroon tie with a beige suit, his hair parted sideways showing off his baldness. That is the perpetual state of Arab manic depression: tremendous pain coupled with bouts of humour and happiness.

In another photo an Indian tent maker told me about his mistreatment by his employers. He would sleep in a small caravan in the yard and share an outdoor shower with some other 20 odd workers. He is still making his tents and he is still hoping of a better life. His co-workers saw my camera and called me over to take his photo, they were joking about how uptight he was. He gave a small, shy smile and agreed to get his picture taken. When I raised my camera, his face changed. The shy smiled became a stoic look. His face was in defiance to how he is being treated; a testament of his will, resilience. He didn’t blink, nor change his face after I took his photo four times. He had the uncanny will to live, to thrive.

These stories are not unique; they are present in every single migrant working in Kuwait. Stories of pain coupled by an unthinkable willingness to live and survive, and most of all thrive. These stories are deeply rooted within the banality of migrant life in Kuwait. A quotidian nature of accepting pain and living through it.