They call me the Woodwose.

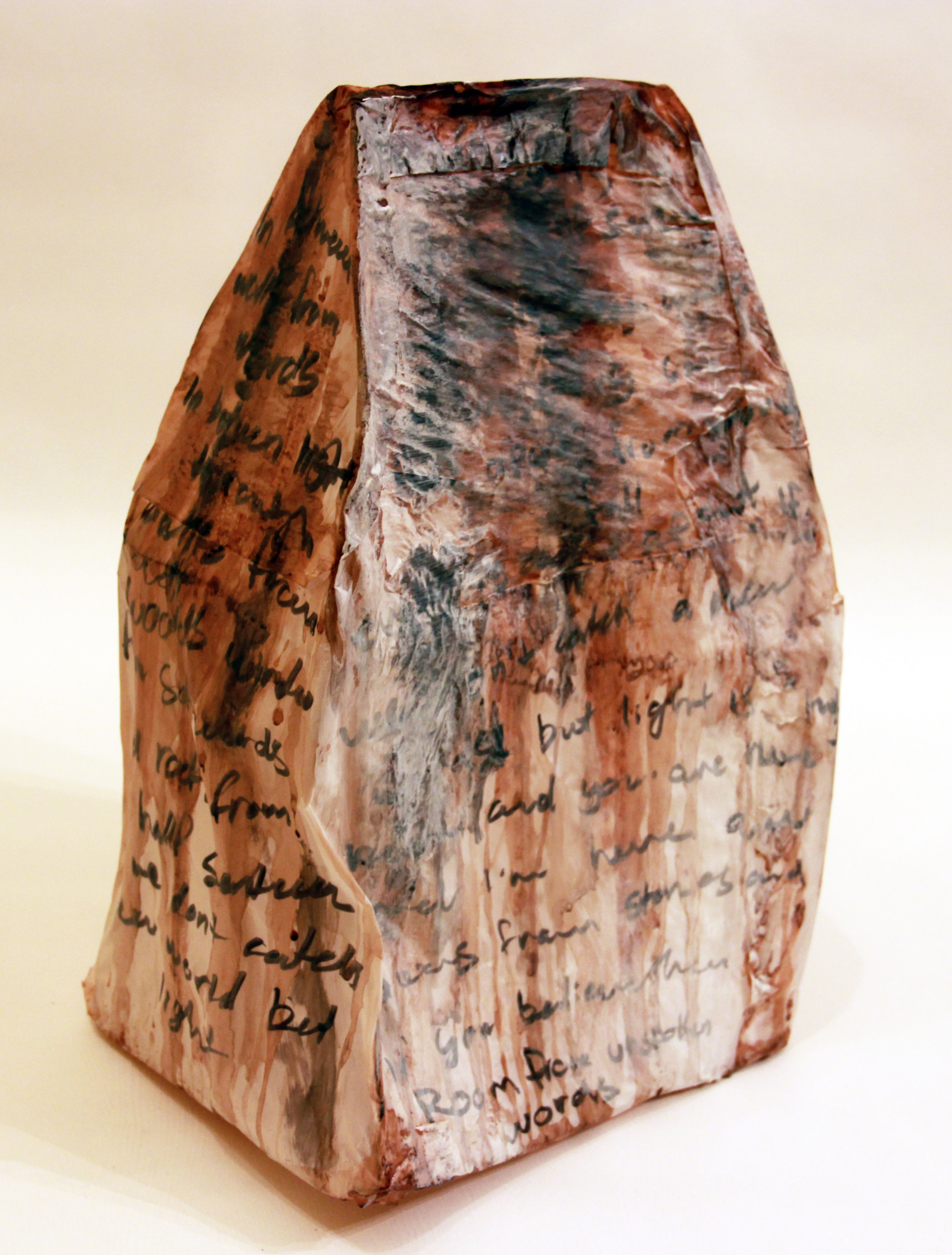

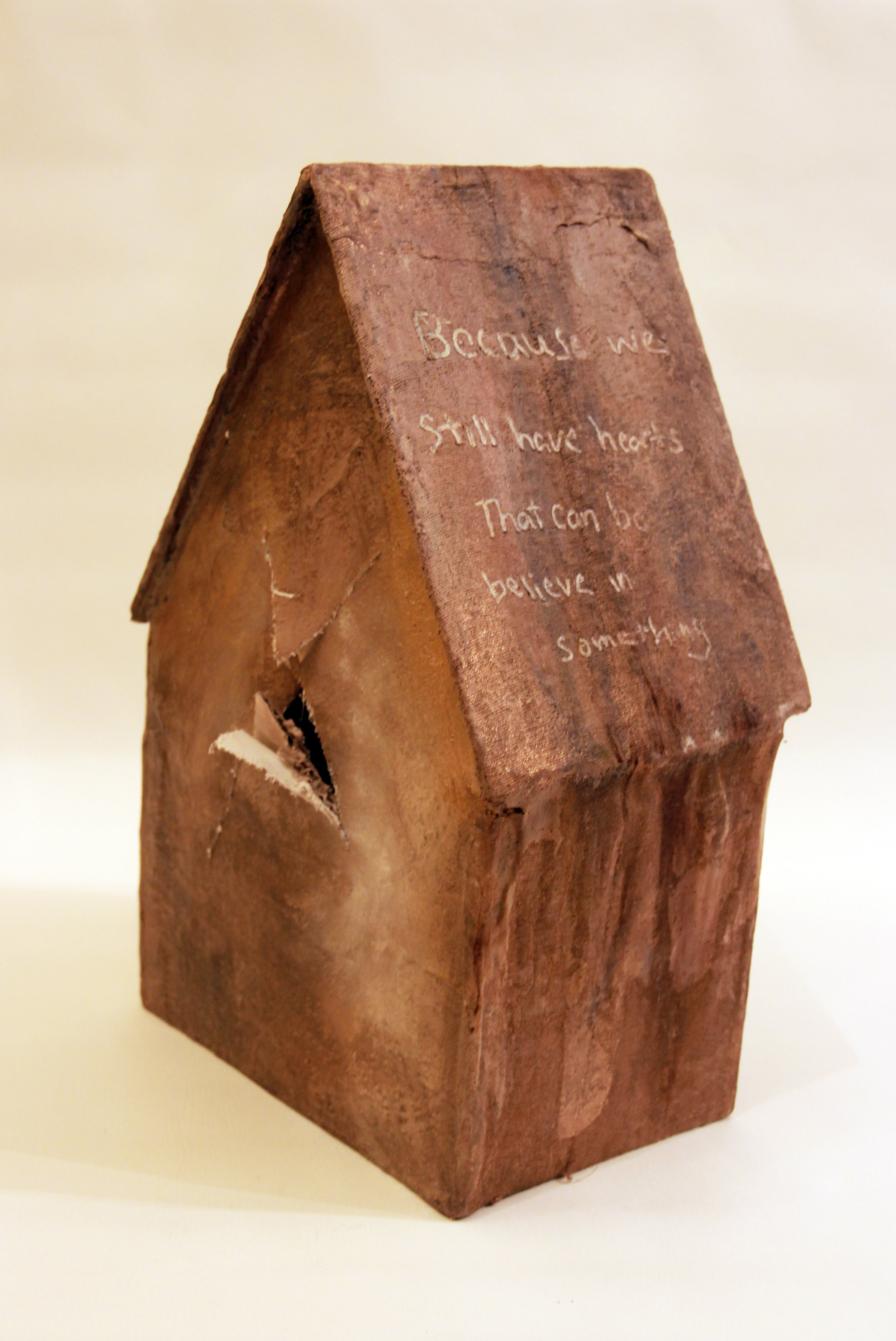

But they know that I am the forest; I am the canopies and the wind and the soil underneath. I have been, ever since I inhabited its heart long ago, and settled in another still, in the heart of the Great Tree.

“I have come,” she says in a voice far too large for her frame, “to purge you, fiend!”

To that I sigh, and pay no thought to the years that the exhale holds. I have heard it a thousand times, from kings and knights and furious farmers alike. I've made their water and their wealth mine, and so have I their harvest and lands.

Their yield is poor this year. Not the fault of rainfall or the sun, but mine. I grow more able to bring suffering upon them, season by season.

Her father owns a nearby land, she says. Her anger is understandable, but she’s a fragile thing. A girl in her homespun skirts and flimsy limbs, with golden hair curiously chopped to her nape. Strange things they are, humans, that a fortnight of starvation could kill them, and yet they defy, and yet they dare.

She comes with a spade, and it becomes clear that no sorcery could flow from those fingertips. She fails on the first day, and she fails on the second. On the third, I ask why, thinking that it’s a redundant thing; because she’s a farmer’s daughter, and I make their crops suffer.

“To be granted knighthood.”

And my belief in the limits of foolishness disappears. It wasn’t a very strong belief to begin with, not with her futile efforts at my sides, digging at roots that recover in instants.

Being a farmer’s daughter isn’t completely irrelevant, I learn on the fourth day, because her mother died. They couldn’t provide what she needed; I took their yield. On the fifth, she cries and I can’t distinguish tears from the sweat running down her cheeks, and it’s the bitter, furious kind because she’s miserable and a little broken. On the sixth day, she learns that I forgot the sight of the sky; and on the seventh, I learn that she can chart it.

Days pass, and she brings apples with her sometimes. When she allows herself to rest, she weaves flowers into her braids. It grows, that hair, but so do my roots, back into the dirt where they belong. Soon I learn her name, and Constance watches as her efforts become vain.

She listens when I scoff and tell the tales of her predecessors. Sometimes she laughs too, at the knight who promised the heart of the tree but fled when it talked, and the old king who led his men to where the horses wouldn’t follow, and tripped into the river while he hailed his call.

When I ask if she’s searching for my weakness in their stories, “Perhaps I am,” she cheekily says. But no, and although I am incapable of emotions beyond sins, no tenderness to be offered to humans, I can see it; that earnestness in eyes that should be set on horizons.

“Find my virtues,” I tell her after months she spends visiting, the secret of uprooting the heart of the woods.

Seven, scattered across lands and seas far beyond her little village. It intrigues her, and she asks where, not how. And it is a little charming how willful the weaker beings can sometimes be. At least she, whose eyes bear something I can’t read, when she’s told in which scorching desert my Patience I’d left, and in the depth of which sea my Honesty dwells, and how high the mountain that holds my Humility is.

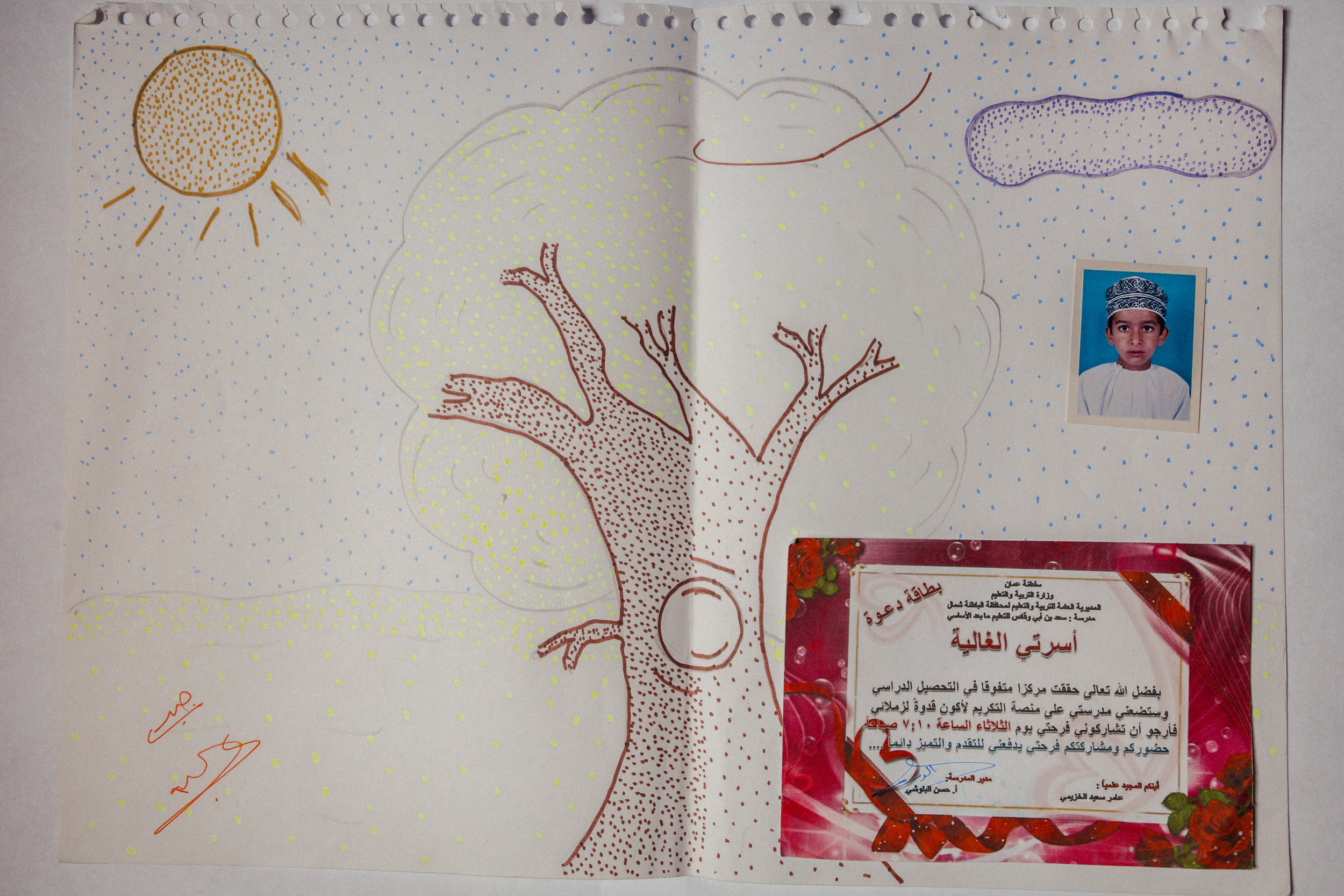

Then they call for her and she heeds. She leaves on a ship, and the wind brings back news of her when he can. She disembarks, and she finds her first companion, a small monkey, on a strange land I must have journeyed during my old life. It wasn’t so robust then.

She spends the year away, guided by voices and the stars. My virtues are gently awakened throughout, but I can’t possess them yet. She is captured and put to suffering for stealing my Charity from a land that honored it far beyond its worth, then she escapes unaided. The wind tells me she finds another companion, a boy, and is taught the way of the sword. Beasts become less frightening, and her sobs more courageous and sparse.

Her laughter comes in abundance, and the freckles on the bridge of her nose become more defined by the sun. She struggles still, against mountains of snow and ice and furious skies. But Constance grows and flourishes and takes the world by a storm.

I hear her curiosity finds ways to discover me, and seas away my secrets unravel in old myths and tales of havoc. She knows that I once had the freedom she seeks, and that I exploited it. I raged and plundered; I remorselessly sinned until that heart was spoiled beyond the capacity of a body to contain.

I begin losing myself, perhaps as she finds me elsewhere. I grow weaker in the entirety of my existence. Their crops prosper and her father writes and sends birds with joy. It appears that it soon would be gone, my vision, but it doesn’t shake me, because the wind sometimes carries her voice, but never the sight of her.

She’s carrying trinkets in the palms of her hands when she returns. Seven of them; little, old things that gleam even in the dead of the night, even to eyes that could see nothing else. I’ve become too weak for the year she spent away to feel as insignificant as it should.

She cries again, and it’s a headache how much she does. “Why have you withered away,” she says, her voice barely wrapped around a sob. “We had an agreement, I was meant to purge you.”

I lie and tell her that it was because she found my virtues that I began dying, but she only weeps harder. “But I have many stories to tell,” she says, and a number of them are about me, small, lost pieces of a past. “You’re not meant to just die yet.”

But I am, because finding my virtues wouldn’t take me, but my own desire to leave would. To leave the tree that took me in when the rest of the world refused is how I am made to die.

She tells her tales as I disintegrate. The bark that kept me for centuries falls apart in the circle of her arms, and the roots that held me dissolved beneath her feet. “Stop crying, you fool,” I say, and it is met by a mess of small laughs and sobs and persevering stories.

“You never told me your Kindness was swallowed by a Kraken. That took a whole crew of pirates to retrieve, and another band of outlaws, too. And a massive carnivorous flower was guarding your Tolerance! I almost decided you could live without it at that sight.”

The Tree vanishes along with all the sorcery that rooted the forest. I feel it in me that it remains behind unchanged, and it could recover and grow without my notoriety keeping it in place. I have lived a burden, and remorse finds its way into me unprompted by the waiting virtues now scattered around her. Her stories are rushed and desperate, and so are her breaths. She breaks a little farther when my past as a human tumbles down her lips. She tells me that she knows and she says it again, that she knows and she knows, and she never says what it is. But it resonates in my body, every piece of the past she unraveled and willfully discovered, that left me with only envy and wrath. I feel it in the form that I undertook, and whether I am a beast or the human I’d once been I don’t know. But I am weaker than I’ve ever been, and even Pride can’t hold me upright against it. My head is cradled on the harsh fabric of her breeches. And my eyes are gone, but she shifts me so they’re looking up. Constance pours Forgiveness on them, and, “Open your eyes,” she says, “Look at the sky, Woodwose, isn’t it beautiful?”

“That, she is,” I say, slipping away under her tears, “That she is."

______

TEXT:

MARYAM M.H

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES