July 1948, Beirut. The State of Israel is created. Britain withdraws from Palestine, formerly their territorial mandate. Fighting breaks out. Palestinians flee into Lebanon and Jordan.

The ninth day of the ninth month finally arrives. My mother tells me we are at war, but I have seen only stars lining the night sky, heard only the tree frog sing outside my window.

Perhaps it is best we not contemplate what is happening at Beirut’s threshold because Ramadan calls us to refrain from talking gossip or even thinking anything negative about others. I try to stamp it from my mind.

This is the first year that I am to fast, which I am of two minds about. I am flushed with pride to be mature enough to pay proper homage to Allah, but I am worried my stomach will get the best of me. It is strange to eat my breakfast before getting dressed, but I consent.

It being a Friday, I spend most of the day lying on the cool tile of the kitchen floor under the table, reading. My brothers are outside in the courtyard by the fig tree, but my mother’s declaration makes me uneasy. The thoughts of guns return. I continue to trudge to the courtyard and gaze up into the sky, yet my searching reveals only white puffy clouds. A dragon. A triangle. A lion. I wonder what a real lion would look like.

Zap! My brother’s football hits me in the temple, almost knocking me to my feet. I retreat before he can cuff me. I seem always to be in his way.

I prefer the kitchen with its stowed herbs, its promise of ashaa, dinner, with my mother already lining the dates on plates. I prefer my books. My father taught me how to multiply large figures in my head. He went to his office today in spite of our Holy Day, in spite of Friday. He is always at work. Yet I find I can do it by myself now. It comes easily to me, like a game. In fact, it is a game. The numbers curl in black lines across my mind’s eye, as though they were lining a page, literal and solid. Two times two will always equal four, no matter what Palestine is called.

My stomach growls and echoes. I am unfamiliar with this sensation. Each growl reminds me of the chopped vegetables on ice, but also of my pledge to Allah to keep the fast. I dowse the fantasy of a slice of cold cucumber, and I gulp down a full pitcher of water my mother offers instead.

“It is fine for a child of your age,” she informs me, but I raise one eyebrow in doubt. Even so, it is abominably hot for May. The tiles warm my toes as the sun pulls itself ever higher. I hear the strains of my brothers’ laughter and whoops, and wonder how they can be so active in this heat. How they can forget about Ramadan. How they can ignore the war. I wish I could take my vest off, but that is not an option in this home.

My thoughts drift toward the salty, cool bite of the sea when my mother calls me for midday prayers. I stand with pride next to my father and brothers as we face Mecca. My father guides me as I kneel and rise, kneel and rise. The sun will soon yield to the moon. Soon we will be breaking our fast. We will start with water and a few dates, and then we shall have a small feast.

“Are you certain you can make it through the afternoon?” my mother asks after we finish prayers. “Observing Ramadan in the seasons with longer, hotter days is more difficult, and you are young yet.”

“No, Mama, I can make it,” I assure her. I click my tongue against the roof of my mouth so it will not feel so dry. She ruffles my hair again and pats me roughly on the back. “My youngest, my baby, is almost a man,” she grins.

I grin back at her. She is my nine-year-old world. I want to make her proud. I want to make Allah, may His Name be praised, proud. I climb the fig tree, full of sweet-smelling fruit, to the roof to await sunset. I hold my belly in anticipation. The sky is blue and clear and hot. I must descend.

We study the Quran as the day grows old. I fidget in spite of myself when the longer Qur’an passages are recited. I usually love the lilt of words mixed with the space of breath in between. This Book is like music to me. Yet today the words about peace confound me, and my thoughts drift once again to what will happen to our country tomorrow.

Twilight finally avails herself to us. I am thankful as we pray. We are blessed. I jump up as the neighbors flood in for the evening meal. I scamper away from their greetings of Ma’brouk, their kisses of greeting. I can only run toward nourishment. I barely taste the food as it goes down.

After the dates, bananas, olives, tabouleh, grape leaves, and a platter of cold meats await me. Food has never tasted so delicious, and it never will again. I know this to be so because today marks many more fasts, and I shall be stronger the more I practice Allah’s will.

That night, after prayers, I stare up at the new moon. Still no sign of bombers. Each year, at the end of Ramadan, we donate five gifts to the needy. It helps us remember the poor, just as fasting helps us remember the less fortunate. Perhaps we will take our traditional Ramadan gifts to the Palestinians this year. I wonder if there are any yet in Beirut. If not, where are they? I wonder how my mother will react to my idea of bringing the refugees gifts.

I hear her murmur to my father, and I sense the worry in her tone. I hear the tears in her voice. Is she weeping over the war? Surely not, our region is always at war. We were at war the year before I was born. Is she weeping over the people coming to stay in our country? It is clear to me that she has sympathy for them, but it is also clear that she does not want them here, with us. If we offer them gifts, they may want to stay. I wonder if Palestine is as beautiful as Lebanon. I wonder if the people crossing our borders miss their homes.

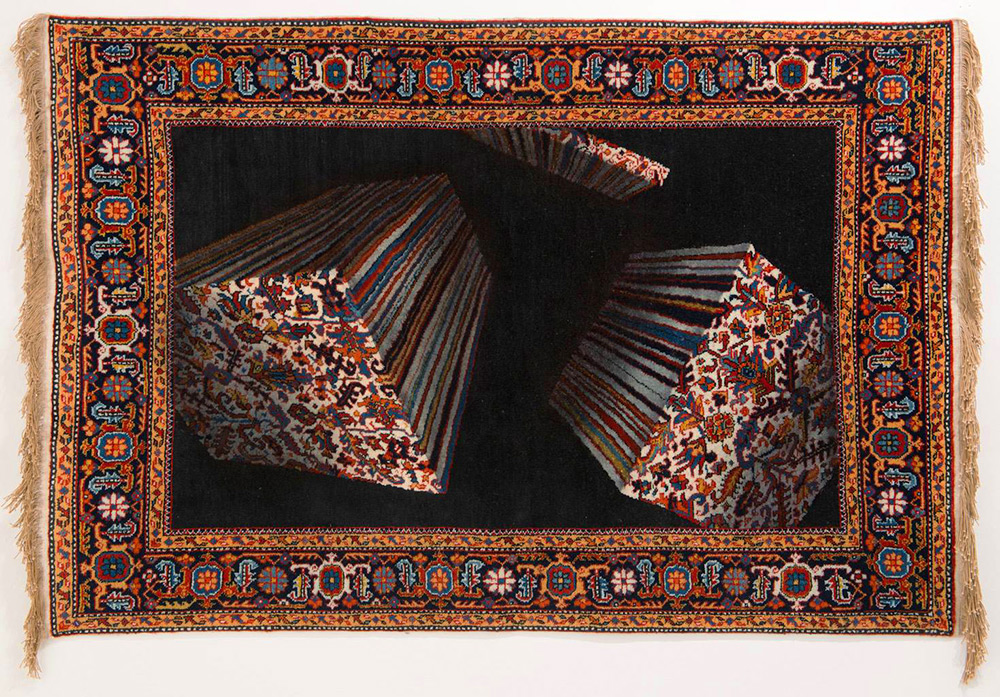

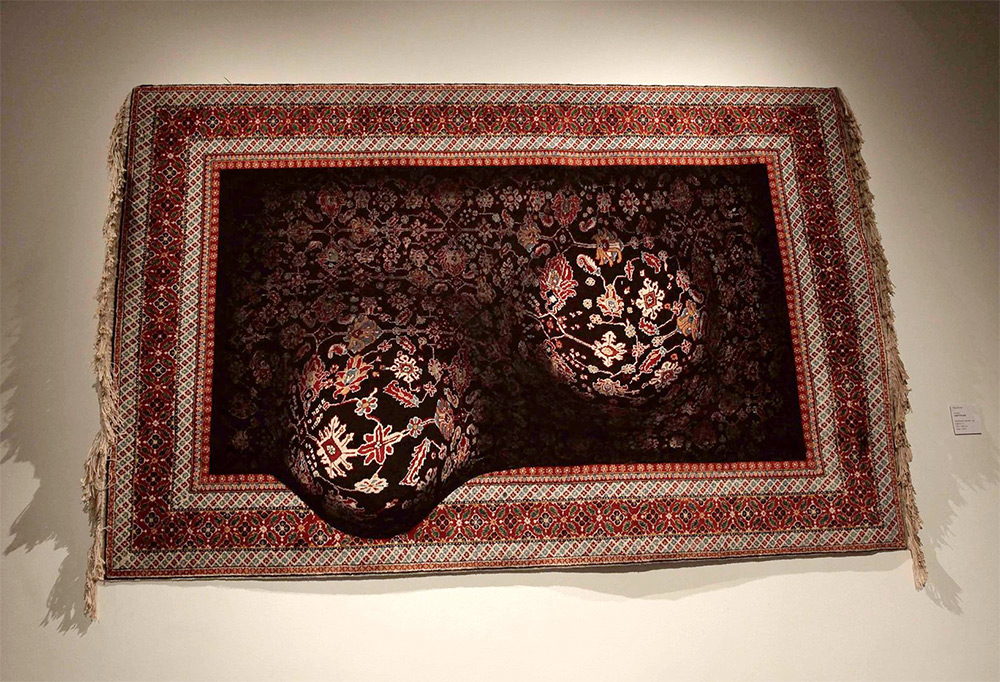

I think not. No land exists as beautiful as our country, full of mountains of cedar, aquamarine waters teeming with fish, clear, clean springs, its souqs overflowing with the scent of spice, its boulevards lined with red-roofed cafes. And my home that the breeze whips through even on hot days like this one, full of tile, bookshelves, rugs of every design—and love.

I creep to the door. I hear the words blight on the land from my mother and temporary from my father. What does blight mean? What does temporary mean? A day, a month, a year? Where are these Palestinians? I have yet to see them.

I continue to wonder if the Zionists will invade our country. Perhaps they are angry at the Palestinians and will come after them. A breeze flows though my open shutters, and I shiver in anticipation. I hope not. It is strange to me that my first Ramadan fast should occur at such a time of violence, that while we are feasting, people are crossing over with all their belongings on their backs. Perhaps with no food at all. Perhaps with no water.

What were they trying to escape? What could have possibly been happening to them for them to leave their houses? I cannot imagine having to leave mine—ever. If Islam means “peace,” I think, why must we fight at Ramadan? Why must we fight at all?

-------

TEXT: KATHRYN BROWN RAMSPERGER

ART: HANNAH KIRMES-DALY / BRUSH & BOW