PHOTOGRAPHY

FILM JOURNAL #2

FILM JOURNAL #1

UNTITLED // JOHARA ALMOGBEL

LINGUA FRANCA #1: ELLIPSES

Writing in his book Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes describes a photograph as the reflection of the photographer an inherent imposing of the photographer’s own dreams, fears, and obsessions into celluloid film (or pixels). Photographing such a seemingly bleak landscape such as Kuwait’s can be difficult, given the country’s oversaturation of skyscrapers and its inherent societal resistance towards being photographed. Being a conservative society, it is also especially difficult to photograph women without asking their permission first. Yet, the beauty of Kuwait lies within its little idiosyncrasies, its overlooked details often overshadowed by its modern razzmatazz; the banal. The exploration of everyday banality, the quotidian, is a fascinating theme to explore through photography. Stories are hidden deep within aged leather shoes and ratted handbags. The reflection of pain through the mundanity of everyday life is a theme that enthrals a person the more they try to delve in it; as Barthes writes, an obsession imposed on a photograph. The theme is further amplified through the motif of loneliness. I, perhaps unconsciously, try to impose scenes of loneliness through the framing of the subjects within the photograph and the usage of black and white film. The monochromatic nature of BW film enhances the feeling of solitude, the contrast of shadows and highlights encapsulates the dichotomy of coming to terms with pain and solitude while trying to live a normal life.

Kuwait is a nation of migrants. Every person living in Kuwait can trace back their roots elsewhere (even though some won’t admit it). Cosmopolitanism has been the driving force behind Kuwaiti culture since its inception in the 18th century. This multi-ethnic melting pot (as cliché as this term can be) is reflected in its music, cuisine and art: ranging from Africa, Iraq, Iran and elsewhere in the Gulf region. That said, Kuwait’s mistreatment of migrant and foreign workers is no secret. It joins ranks with other oil-rich Gulf states in its systematic mistreatment of migrants, demonstrating appalling human rights abuses through withholding of salaries from employers and institutional racism from the government.

For the most part, migrant workers built Kuwait’s infrastructure, a reflection of the aforementioned cosmopolitanism. Workers from Southeast and Far East Asia and elsewhere from the Middle East constitute about 68% of the population. The irony lies within the majority of the non-Kuwaiti population and the nature of mistreatment they receive. Migrant workers serve as the foundation of Kuwaiti society; a society that, alongside Kuwaiti citizens, would not have come to existence without their help. Their sweat, tears and blood helped build Kuwait to what it is today. Yet we, as a Kuwaiti society, often overlook them. We see them as nothing more than a set of hands doing a job, devoid of humanity. We owe migrant workers everything for helping us build our country.

For this photoset, I went to the souq (Market) of Mubarkiya, the oldest known souq in Kuwait, predating the rapid urbanisation that swept the country during the 50’s after the discovery of oil. Within the old brick and concrete roads of the souq lie the smells of old Kuwait: fishmongers, butchers, fruit sellers and fabric shops, right in the heart of Kuwait’s booming downtown financial district. This juxtaposition of history is also reflected through market goers; selfie sticks and Segway scooters alongside old dates sellers and incense merchants; fathers taking their children to the old coffee shops to drink tea and tell the stories their fathers told them; families eating kebabs and shawermas in the same restaurant they’ve been going to for the past 30 years. The character of the souq is reflected upon the various nationalities of merchants there: Indian Bohra gold sellers, Iraqi and Iranian fruit and food sellers, Egyptian butchers, and Syrian fabric sellers. Mubarkiya is a microcosm of Kuwait’s cosmopolitan history.

My fascination with photographing the banal led me to conversations and photos with the various nationalities that inhibit the souq. A Syrian fabric shop owner, the one who is posing with a cigarette in his mouth, came to Kuwait at a young age and started working with other Syrians in the business. He still has family back in Syria and, as he looked away (perhaps out of respect) and inhaled his cigarette, told me about his attempts at applying for a visa for his nephew in order to get him out of Aleppo. His pain was tangible, it almost had a taste of stale cigarettes chain-smoked to help him cope. A pain reflected by his blackened out face; a face succumbing to hopelessness, numbness. The unfortunate banality of his pain contrasted by his sense of humour when he told me he chooses to dress smart because no one would buy from a messy looking merchant. He wore a bright patterned maroon tie with a beige suit, his hair parted sideways showing off his baldness. That is the perpetual state of Arab manic depression: tremendous pain coupled with bouts of humour and happiness.

In another photo an Indian tent maker told me about his mistreatment by his employers. He would sleep in a small caravan in the yard and share an outdoor shower with some other 20 odd workers. He is still making his tents and he is still hoping of a better life. His co-workers saw my camera and called me over to take his photo, they were joking about how uptight he was. He gave a small, shy smile and agreed to get his picture taken. When I raised my camera, his face changed. The shy smiled became a stoic look. His face was in defiance to how he is being treated; a testament of his will, resilience. He didn’t blink, nor change his face after I took his photo four times. He had the uncanny will to live, to thrive.

These stories are not unique; they are present in every single migrant working in Kuwait. Stories of pain coupled by an unthinkable willingness to live and survive, and most of all thrive. These stories are deeply rooted within the banality of migrant life in Kuwait. A quotidian nature of accepting pain and living through it.

CHILDREN OF BAHRAIN // HAYAT

THE KING, THE DREAM AND THE CHICKEN CAGE // LEEOR OHAYON

This essay is an on-going first chapter from a long-term project, which follows Mizrahi Jewish communities since the first wave of departure from the Arab world in 1949. A two millennia old civilisation that stretched a diverse linguistic and cultural space, from Morocco to Iraq, from Yemen to Libya, numbering a million souls, which has dwindled to an estimated 8 or 9,000 souls today. The project serves to be a reflective portrait of the former Jewish communities of the Arab world at the turn of the 21st century, what has changed and where are we going, what have we lost and what have we gained. To create a comprehensive catalogue of work that allows for future Mizrahi Jews to identify with, in a world that leaves little room for their acknowledgement. Newer generations find themselves caught between the contradictions of the Middle East conflict and its strive for homogenous identity blocs of “Arab” or “Jew” on one hand, and the Ashkenization of mainstream Judaism on the other. Creating an irreversible havoc on the ancient indigenous Jewish identities of the Middle East and North Africa.

The King, the dream and the Chicken cage serves as a portrait of Moroccan-Jewish identity in southern Israel today, nestled in the development towns of the periphery. An identity still zealously guarded, flaunted with pride but subject to the cultural hierarchy anchored into the Israeli environment, which has undoubtedly moulded and transformed Moroccan identity within a generation. Soon-to-be-brides sit patiently as the last link to Morocco, a grandmother or mother, presses henna into her psalms to signal her transition to married life. Men in Chinese made Fez hats sipping Coca-Cola in a community hall, code switching between Moroccan Arabic, Hebrew and French. Signs of an identity refusing to give way to a wider Western –Israeli identity, but one that is ultimately waning with each generation that knows only the Eurocentric education system in which he or she was raised, and that system’s definition of what it means to be Moroccan.’

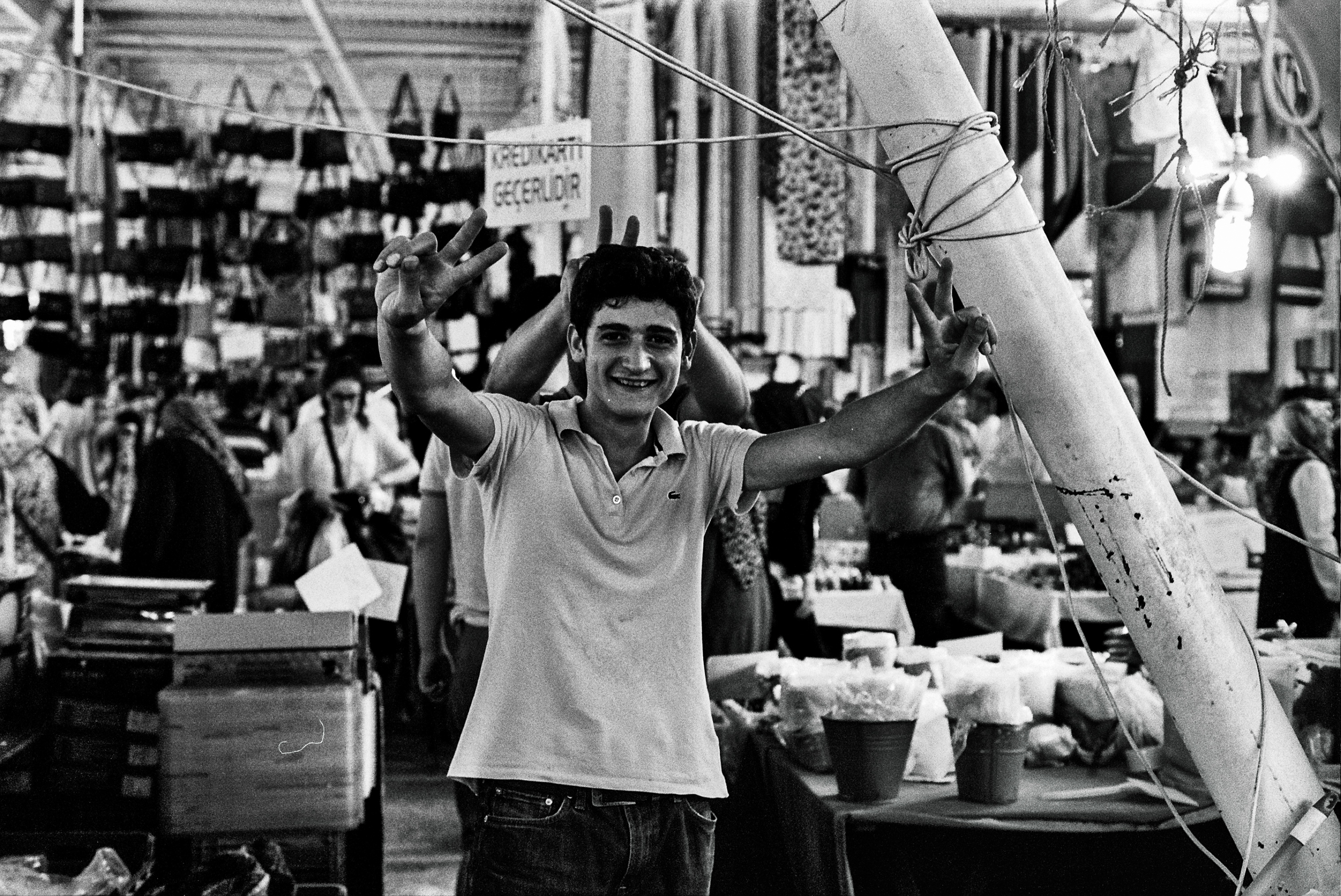

TURKEY // MESHARI

PINK BITS // HAYAT

SINAN COUNTY // DANIA HANY

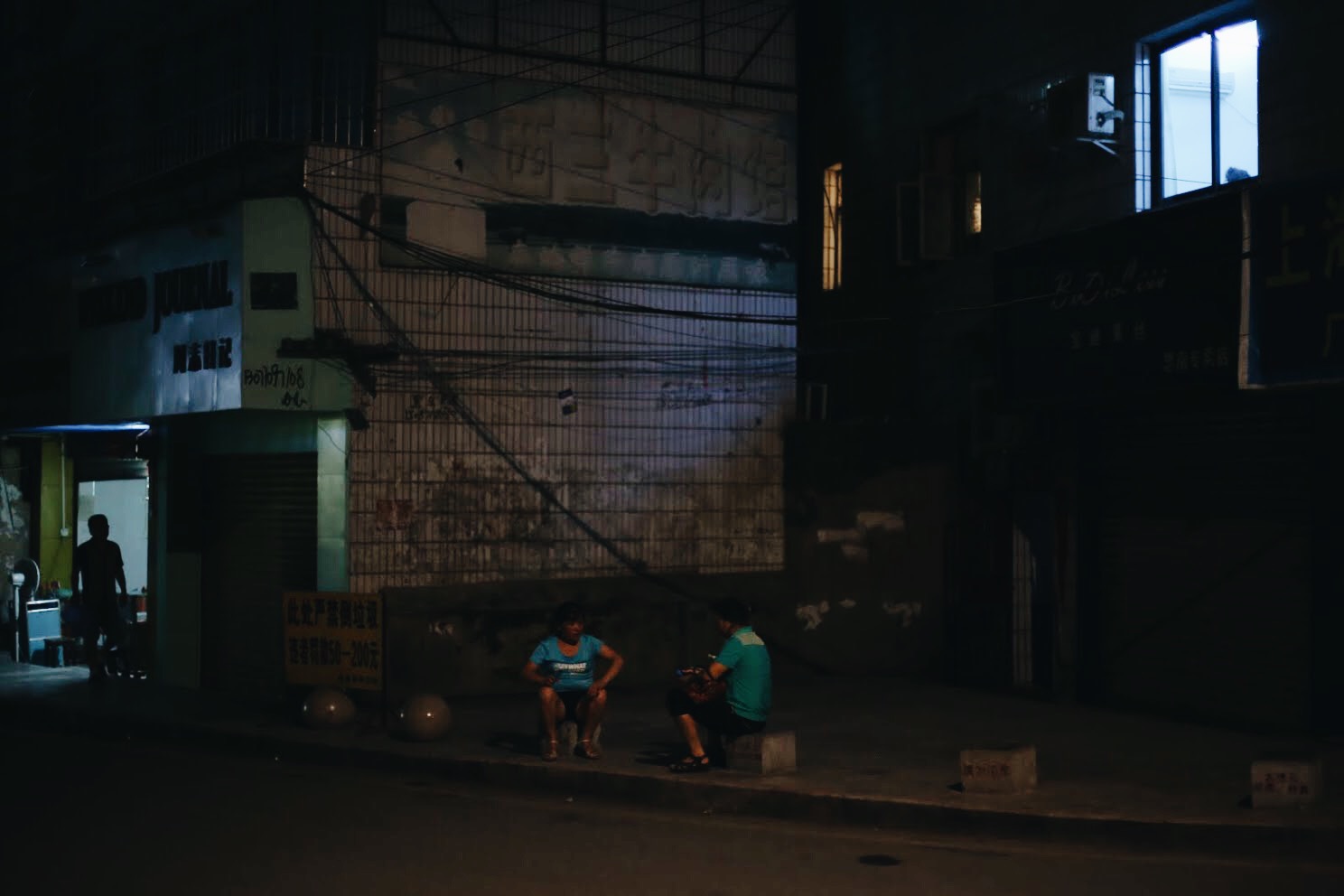

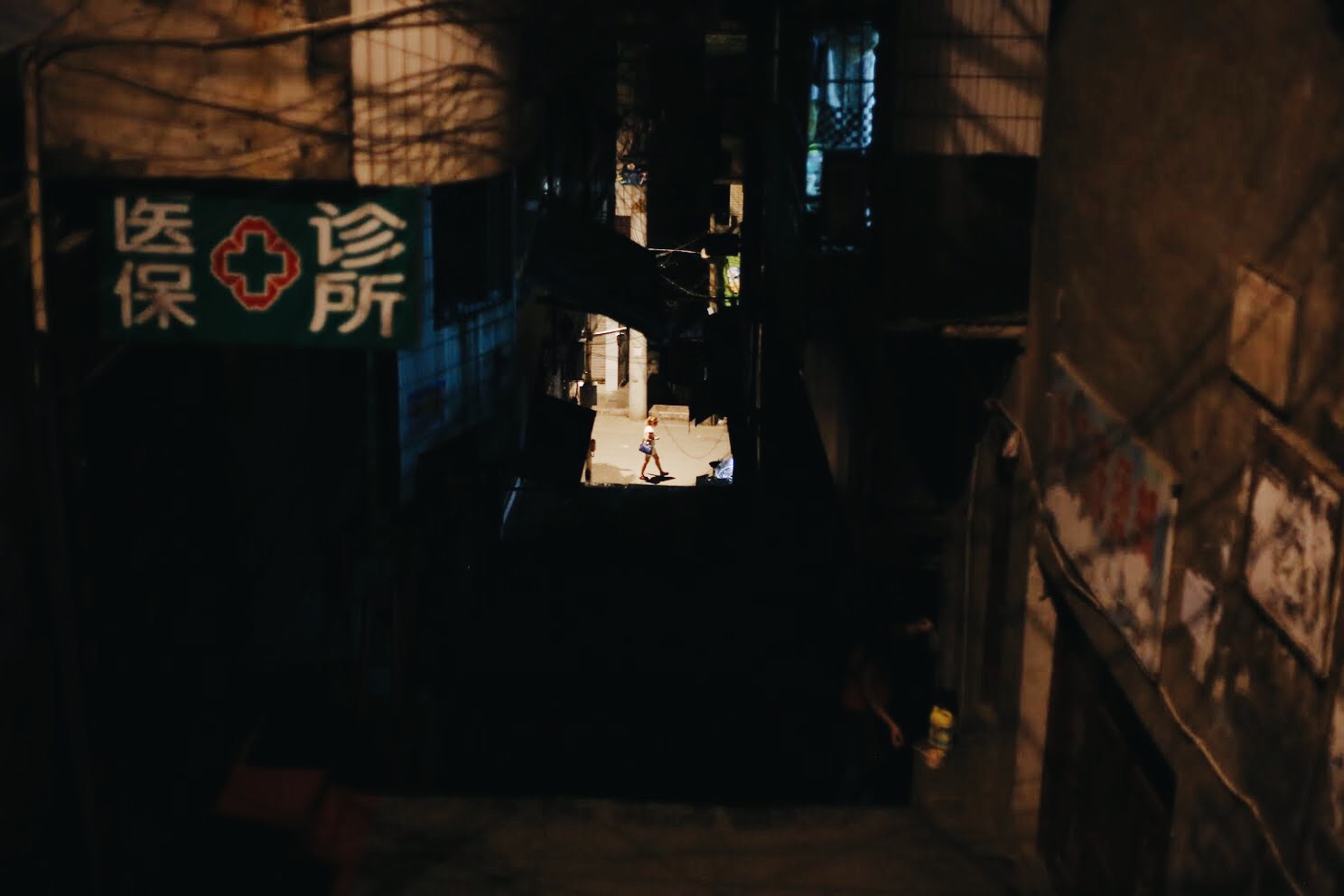

In the south of China, located in Guizhou province is the county of Sinan, a small city build entirely in the middle of the mountains. I spent exactly 9 days there for a teaching project in Sinan's high school.